Intentionally Defective Grantor Trusts

by Steve Goodman

CPA, MBA – President & Chief Executive Officer

Contact Steve today for more info.

While the name intentionally defective grantor trust (IDGT) may sound like an odd name for a powerful estate tax reduction technique, it is very descriptive. Trusts are subject to multiple forms of taxation. Two specific forms are estate taxes and income taxes. Estate taxes are assessed upon death. Income taxes are annual events. When one establishes an irrevocable trust, the trust typically removes an asset from estate tax consideration and the trust pays its own income tax bill. The IDGT is appropriately named because while it complies with estate tax provisions, it is intentionally defective for income tax regulations. The defect forces the grantor to pay the income tax liability rather than the trust.

Background

IRS regulations specify different tax rates for individuals and trusts. They have for many decades. Decades ago, the tax rate for individuals was much higher than it was for trusts. Naturally, estate planning focused on removing assets from personal ownership and into trust ownership. This allowed any income generated by assets in the trust to be taxed at the lower trust rate.

In recent decades, personal tax rates have been reduced below those of trusts. This change in relative tax rates has created a desire to shift taxable income from trusts to personal income. The Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 has temporarily raised the estate tax exemption. This has temporarily relieved many, but not all, families of means of the need to reduce their estates for estate tax purposes. The prospects of a reduction of the estate tax exemption in 2026 make estate reduction techniques even more time critical. Many times, existing legal arrangements are grandfathered when regulations change.

There is one additional factor in play. The tax code not only offers different rates for personal taxes and trusts but also identifies similar but not precisely the same conditions for determining ownership for estate tax and income tax purposes. As a result, it is possible to develop terms of a trust that allows the trust to own an asset for estate tax purposes while allowing the grantor to own the very same asset for income tax purposes. This reality created the basis for the intentionally defective grantor trust. The trust is designed to fail the conditions established by the IRS that require the trust to pay its own income taxes.

Why it Works

The IDGT is attractive because it does the following:

- It permits the grantor to increase the amount of the transfer to future generations by paying the income taxes generated by assets held in the trust. These tax payments are not considered gifts, yet by paying the trust’s tax bill, the grantor is effectively increasing the net contribution to the trust’s beneficiaries. In other words, it permits the trust to retain the maximum amount of income generated by the trust’s assets.

- Because the grantor owns the IDGT for income tax purposes, the grantor can sell assets to the trust without triggering income taxes on the assets’ built-in gain. Selling assets to a trust instead of gifting them preserves the grantor’s estate tax exemption to transfer other assets at death, tax-free.

- It removes the asset(s) placed in the trust of the grantor’s ownership and estate. The trust is irrevocable. Assets are not attachable by a normal creditor.

- Selling an asset to the trust freezes the value of the asset. The transaction essentially converts a growing asset, typically a privately held business or income-producing property, into a bond equivalent. The asset growth becomes the property of the trust. The grantor receives a fixed income stream.

- Transfers are often made at a discount to the fair market value of the asset. The grantor will not transfer full control of the asset to the trust.He/she will retain enough control or ownership to diminish the value of the asset held by the trust. The combined market value of the holdings of three equal minority partners in business is less than the value of the same business held 100% by one owner.

An IDGT is drafted and an asset is transferred into the trust. The asset should be an income producing asset or one that is expected to greatly appreciate in value. Privately owned businesses or income-producing real estate are most often the assets of choice. When gift exemptions are high, as they temporarily are due to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, a grantor has the option of a gift, a sale, or a gift and sale combination.

In most cases, the grantor wants to preserve as much of his/her unified exemption amount as possible. The grantor wants the IRS to consider the transfer as an asset sale. The solution is an arrangement by which the trust buys the asset from the grantor. Typically, the sale is in return for a promissory note from the IDGT back to the

Grantor. The process starts with a valuation of the asset by someone the IRS will find credible.

The grantor wants to structure the asset sale such that the asset value is reduced for sale purposes. This is done by diminishing the asset in a way that will warrant a discounted valuation. One popular way with closely-held businesses is to split the ownership into voting and non-voting interests. The non-voting interests are sold to the IDGT. Typically, the grantor also reserves the right to substitute assets of equal value to the trust. The substitution power is one way to qualify an otherwise irreversible trust as an IDGT and also provides great flexibility.

The IRS has begun to take a hardline approach to discounted valuations in recent years. Many estate planners seek to test the limits of IRS scrutiny in valuing IDGT assets. The IRS and some legislators want to deny the ability to sell an asset to an IDGT for less than fair market value. As of mid-2018, this has not changed and is unlikely to do so under a Republican president. While more attractive at a lower valuation, the IDGT would still be an effective strategy at a full market asset valuation.

If the asset is sold to the IDGT, rather than gifted, the trust is first seeded with a gift that is one-tenth the value of the asset to be sold to the trust. This is a rule of thumb based on case law. To be respected by the IRS, the sale transaction must be “arms-length”.While not an official rule, many practitioners feel that trust with assets equal to 10% of the value of the assets sold will cause the transaction to be arm’s-length. If the IDGT holds no assets, it would not be reasonable for the grantor to sell an asset to the trust in exchange for only a promissory note.

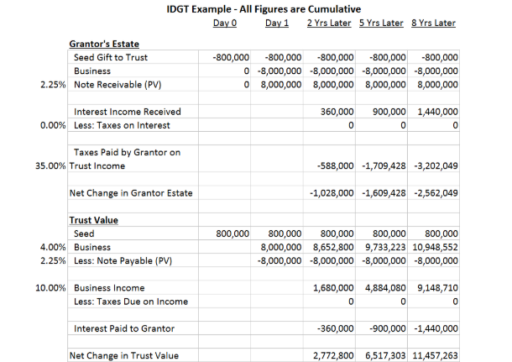

Assume that a grantor seeks to transfer business with a market value of $8 million to his/her children and/or grandchildren. The grantor will seed the IDGT with $800,000 as a gift. The trust and the grantor will then negotiate a deal for the business. The grantor has considerable flexibility in how the deal is structured.

The most common deal is a 9-year, interest-only promissory note with a balloon final principal payment. The IRS issues a monthly interest rate schedule of minimally acceptable interest rates for various transactions. Interestingly, not all trusts employ the same schedules, even if the terms of the transactions are the same. The IRS schedules generally list three rates; one for up to 3 years, one for 3 years to 9 years, and one for over 9 years. The trust and the grantor have two concerns. The first is that it is more favorable than the grantor remains alive for the balance of the payments. The second is that when offered the same low-interest rate for 3 years up to 9 years, the optimal answer is usually 9 years.

The age of the grantor and the income potential of the asset become significant factors in determining the structure of the purchase agreement.

Let’s return to the $8 million business. Assume that the current annual IRS interest rate for a 3 to 9-year loan is 2.25% and the business throws off $800,000 annually in profits. The worst case annual loan payment is 2.25% x $8 million or $180,000/year. If the trust uses a portion of the business income to pay down the principal, it could be less.

One of the reasons the grantor established the IDGT was to minimize his/her estate taxes. Let’s consider how the grantor fared in this example. The day the transaction takes place, the grantor’s estate shows a reduction of $8 million for the asset he/she sold to the trust. But offsetting that asset is a note receivable for the same $8 million. This “freezes” the asset value in the estate at $8 million. Meanwhile, all the income and appreciation on the asset accrue in the trust, outside the estate.

Of particular interest is that since the grantor trust is defective for income tax purposes, the sale of the asset to the trust is treated as a sale from the grantor to the grantor. That is, the IRS looks at the sale as a non-transaction. Therefore, no capital gains taxes are due based on the transfer. For the same reasoning, the interest payments made by the trust to the grantor are also not taxable.

Looking 2 years later, the benefits begin to appear.

- The business is now worth more than $8 million. Assuming it has kept pace with inflation and shown some organic growth, we assume it has grown by 4% annually. The $8 million business is now worth $8.65 million. Since it no longer belongs to the grantor, the increase in business valuation does not count against the grantor’s estate exemption.

- The PV of the loan may have changed as two years of loan payments have been made. The two $180,000 payments have been added to the estate value. For the sake of simplicity and presentation, the example assumes the present value of the loan remains $8 million. In practice, $8 million due in 9 years is worth less than $8 million in current dollars. The interest rate allowed by the IRS may understate the real-world discount rate one would apply to calculate the present value of the note.

- The interest payments are non-taxable income.

- The grantor pays the taxes on the business income. We assumed the business threw off $800,000 annually when the transaction was consummated. If we assume profits also grow at a 4% rate, the grantor pays federal and state taxes on $800,000 in Year 1 and $832,000 in Year 2. The tax bill can run an additional $300,000 to $350,000 per year, thereby reducing the grantor’s estate by roughly another $650,000 over two years.

- The earnings upon which the grantor paid taxes are fully retained by the trust. After two years, the trust has gained almost $2.8 million, of which $800,000 was the initial seed gift.

The presentation shows the growing transfer of assets from the grantor to the trust. The trust benefits from the growth of the asset and the asset’s ability to generate cash in excess of the amount required to pay the interest payment. The trust is relieved of paying income taxes, so it can keep all that it earns after paying the interest to the grantor. Should the trust require capital to keep current with the payments due to the grantor, it can use the asset as collateral. It can borrow money from anyone with the exception of the grantor. If it borrows money from the grantor, the IRS may consider this the grantor paying the grantor. The penalty would be to consider the entire transaction to be a gift.

The grantor’s estate declines over time, assuming no other significant assets. The estate has given up any growth associated with the business. It pays taxes on the asset’s earnings. The tax the grantor pays on the business earnings is a hidden gift.

Over a period of just 8 years, the grantor’s estate has been reduced by almost one third the value of the initial asset.10% of that is the seed gift. The rest results from the taxes paid for the business. Meanwhile, the trust has grown from nothing to nearly 150% of the value of the asset. The trust now has ample cash to make a substantial payment to the grantor when the balloon payment comes due. Assets in the trust can be used as necessary to pay the balance of the note.

Creating Intentional Defects

There are several ways to create a trust that fails the ownership test for income tax purposes. An astute attorney will structure the trust document to leave the door open to reverse the defect. Should the grantor run into financial difficulty, a reversal will require the trust to pay its own income taxes.

- The grantor retains the power to reacquire assets from the trust and substitute other assets of equal value. This is known as the ‘substitution power’.

- The grantor retains the right to borrow from the trust without adequate interest or security.

- The grantor authorizes the trust to pay premiums on a life insurance policy on the grantor.

Each of these provisions will cause the trust to be owned by the grantor for income tax purposes, but not for estate tax purposes.

Considerations

- Grantor trusts are one of only a small number of trust types allowed to own shares in S-Corps. There is no problem putting an S-Corp into an IDGT.

- There are similar trusts that accomplish similar goals. Specifically, GRAT’s (Grantor Retained Annuity Trust) and IDGTs have overlapping purposes. (See separate article on GRATs in this Estate Planning Section)

- A sale to an IDGT that does not follow the IRS interest rules, fails to lift the initial 10%, or attempts to use a low valuation on the asset runs the possibility that the IRS will reclassify some or all of the transaction as a gift. Gift exclusions are limited and highly valued by people of means. Estate planners are particularly mindful about how to best use this valuable resource.

- Assets sold to the trust can provide leverage for the grantor. Consider an asset sold to the trust for $5 million in exchange for a 9-year note. The grantor’s cost basis on this asset is $1 million. By year 8, the asset has a market value of $8 million. The grantor buys the asset back from the trust exchanging the asset for a high-basis asset such as $8 million in cash or marketable securities. By buying back the asset and substituting cash, the grantor’s beneficiaries will inherit the asset with “stepped-up” basis equal to its fair market value at death, and not the grantor’s original cost basis.

- The trust can make disbursements to the beneficiaries during the life of the trust. Income from the asset does not need to sit in the trust’s account.

- A grantor who wishes to retain control over his/her business can transfer non-voting interests to the trust. The non-voting interests can be sold to the IDGT trust allowing the grantor to retain control over the business via the voting interests. The non-voting shares may also reduce the market value of the business when sold to the trust. Even S-Corps are permitted to issue voting and nonvoting shares.

- Tax law is not settled regarding a sale to an IDGT in exchange for a promissory note. If challenged by the IRS, a grantor or his/her estate could face tax court with more unknowns than an attorney might prefer.Premature death of the grantor is one such gray area. The IRS can view death as terminating a grantor trust. This could make the estate liable for any capital gains associated with the underlying asset. There is IRS guidance on some aspects of IDGTs.However, without established rules on certain aspects of selling assets to IDGTs (rather than gifting), some uncertainty will remain until resolved in the courts or by congressional action.

CPA, MBA – President & Chief Executive Officer

About Steve Goodman

For more than 30 years, Steven has provided insightful solutions to the challenges of business succession, wealth preservation and charitable planning, focusing on the needs of owners of closely held businesses and high net worth individuals.

He's been featured in the New York Times and is an accomplished speaker and has presented over the years to many organizations and professional groups on efficient business succession, estate planning issues and tax strategies. Steven is a CPA who was vice president of the Trust and Investment Division of JP Morgan Chase and a supervisor for KPMG Peat Marwick, and holds an MBA from Fordham University.